The UK has been ranked 10th from bottom in a global league table of 39 developed nations assessing work-life balance, despite British employees working some of the shortest hours in the study.

The finding comes as millions of workers return to their jobs after the summer holiday period, highlighting a wider concern about how effectively UK workplaces support life outside of work.

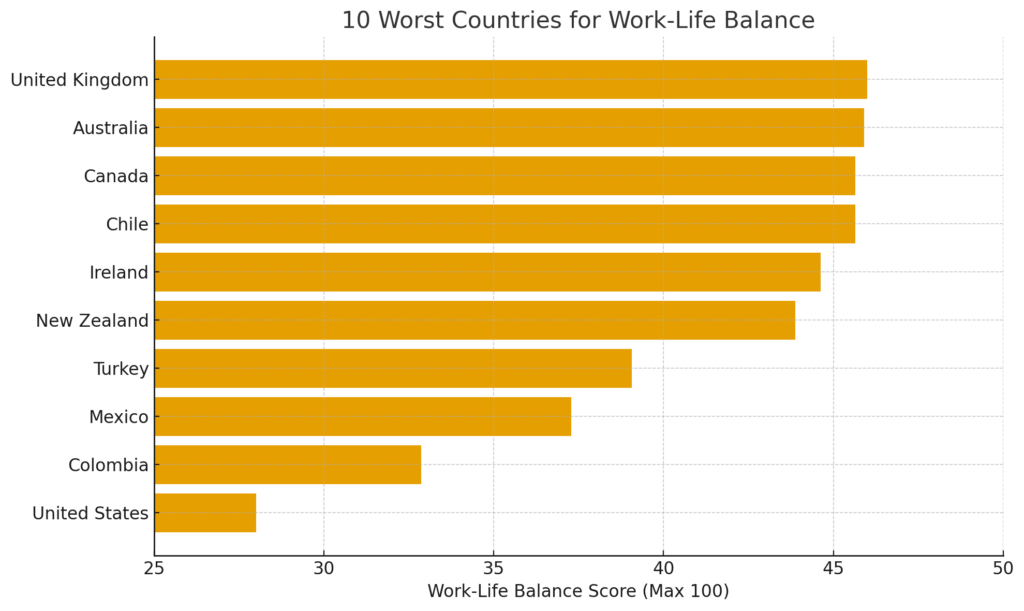

The analysis, published by comparison site Compare the Market and based on data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and World Happiness Report, scored the UK 45.99 out of a possible 100. That placed it just ahead of Australia, Canada and Ireland, but behind much of Europe and well below top performers such as Finland, Norway and Denmark.

Shorter Hours, Lower Support

UK employees average 1,524 working hours per year, significantly fewer than in the United States, Mexico or Colombia, where workers clock in more than 2,000 hours annually. But despite having more time off the clock, British workers still face relatively limited support when it comes to parental leave and paid time off.

The study identified the UK’s maternity pay rate of 31.1 percent and paternity pay rate of 20.4 percent as key reasons for its low overall score. Finland, by contrast, offers extensive parental leave — up to 161 weeks of paid maternity and 16 weeks for fathers — alongside 36 paid days off per year, short commutes and high leisure time.

Workers in Finland also report a happiness score of 7.7 out of 10, compared with 6.728 in the UK.

Cultural and Policy Gaps

Experts have long warned that work-life balance is shaped by more than just contractual hours. Workplace strategist Neil Usher has said employers often focus on flexibility without addressing the deeper organisational culture. He was reported as saying that if people are afraid to use their leave or feel judged for logging off, then flexible policies mean little in practice.

Government policies also play a role. The UK’s statutory maternity pay, which allows up to 39 weeks with reduced income, remains far below that of several European countries. Paternity leave is limited to two weeks for most employees, unless their company offers an enhanced package.

Work-Life Tensions Intensify Post-Pandemic

Post-pandemic working patterns have helped some employees gain flexibility, but many others report longer working days and a blur between work and home life.

Research from the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) found that while hybrid and remote working arrangements have grown, around half of workers say they struggle to switch off at the end of the day. The same study found that burnout was rising fastest in roles without clear boundaries or support.

A Mental Health Foundation report also noted that poor work-life balance is one of the strongest predictors of stress, with long-term implications for mental health, job satisfaction and staff turnover.

What Employers Can Do

Employers looking to improve work-life balance for their workforce can focus on several key areas:

Reviewing leave policies: Organisations should ensure that staff are aware of and feel able to take their full entitlement to paid leave, including annual leave and parental rights. Enhanced parental leave policies can help attract and retain talent, especially among younger workers.

Normalising flexibility: Beyond remote work, this includes flexible start and end times, compressed weeks, and job shares. Crucially, leaders must model these behaviours and encourage a culture where flexibility is not seen as slacking.

Setting boundaries: Expectations around email response times and availability outside of working hours should be made clear and realistic. “Always on” cultures erode wellbeing and productivity over time.

Monitoring workloads: Regular check-ins to assess whether employees have manageable workloads can help prevent burnout and encourage early intervention.

Providing wellbeing support: Employee assistance programmes, mental health resources and line manager training can all play a role in supporting balance, particularly during life transitions such as becoming a parent or caring for relatives.

The CIPD also recommends that employers consider offering sabbaticals, paid volunteering days or wellbeing hours as part of a broader package that supports both retention and mental health.

Broader Change May Be Needed

While employers have an important role to play, the UK’s position in the global ranking also reflects a wider lack of national policies compared with other developed countries. Nordic nations score highly not only for leave and wellbeing, but also for structural supports such as subsidised childcare, generous social protections and a culture that prizes downtime.

The UK Government has taken some steps toward improving balance, including proposals to make flexible working a day-one right and pilot schemes for a shorter working week. However, campaigners argue that stronger statutory entitlements and better enforcement are still needed.

Calls for improved parental leave pay, extended paternity leave and formal recognition of the right to disconnect have been growing across trade unions, employee groups and MPs.

The UK’s place in the bottom third of the global index may serve as a reminder that long working hours are not the only cause of imbalance. Without better policies, stronger protections and supportive cultures, even short working weeks can leave employees exhausted and disengaged.